I.

Kaj Sotala has an outstanding review of Unlocking The Emotional Brain; I read the book, and Kaj’s review is better.

He begins:

UtEB’s premise is that much if not most of our behavior is driven by emotional learning. Intense emotions generate unconscious predictive models of how the world functions and what caused those emotions to occur. The brain then uses those models to guide our future behavior. Emotional issues and seemingly irrational behaviors are generated from implicit world-models (schemas) which have been formed in response to various external challenges. Each schema contains memories relating to times when the challenge has been encountered and mental structures describing both the problem and a solution to it.

So in one of the book’s example cases, a man named Richard sought help for trouble speaking up at work. He would have good ideas during meetings, but felt inexplicably afraid to voice them. During therapy, he described his narcissistic father, who was always mouthing off about everything. Everyone hated his father for being a fool who wouldn’t shut up. The therapist conjectured that young Richard observed this and formed a predictive model, something like “talking makes people hate you”. This was overly general: talking only makes people hate you if you talk incessantly about really stupid things. But when you’re a kid you don’t have much data, so you end up generalizing a lot from the few examples you have.

When Richard started therapy, he didn’t consciously understand any of this. He just felt emotions (anxiety) at the thought of voicing his opinion. The predictive model output the anxiety, using reasoning like “if you talk, people will hate you, and the prospect of being hated should make you anxious – therefore, anxiety”, but not any of the intermediate steps. The therapist helped Richard tease out the underlying model, and at the end of the session Richard agreed that his symptoms were related to his experience of his father. But knowing this changed nothing; Richard felt as anxious as ever.

Predictions like “speaking up leads to being hated” are special kinds of emotional memory. You can rationally understand that the prediction is no longer useful, but that doesn’t really help; the emotional memory is still there, guiding your unconscious predictions. What should the therapist do?

Here UtEB dives into the science on memory reconsolidation.

Scientists have known for a while that giving rats the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin prevents them from forming emotional memories. You can usually give a rat noise-phobia by pairing a certain noise with electric shocks, but this doesn’t work if the rats are on anisomycin first. Probably this means that some kind of protein synthesis is involved in memory. So far, so plausible.

A 2000 study found that anisomycin could also erase existing phobias in a very specific situation. You had to “activate” the phobia – get the rats thinking about it really hard, maybe by playing the scary noise all the time – and then give them the anisomycin. This suggested that when the memory got activated, it somehow “came loose”, and the brain needed to do some protein synthesis to put it back together again.

Thus the idea of memory reconsolidation: you form a consolidated memory, but every time you activate it, you need to reconsolidate it. If the reconsolidation fails, you lose the memory, or you get a slightly different memory, or something like that. If you could disrupt emotional memories like “speaking out makes you hated” while they’re still reconsolidating, maybe you could do something about this.

Anisomycin is pretty toxic, so that’s out. Other protein synthesis inhibitors are also toxic – it turns out proteins are kind of important for life – so they’re out too. Electroconvulsive therapy actually seems to work pretty well for this – the shock disrupts protein formation very effectively (and the more I think about this, the more implications it seems to have). But we can’t do ECT on everybody who wants to be able to speak up at work more, so that’s also out. And the simplest solution – activating a memory and then reminding the patient that they don’t rationally believe it’s true – doesn’t seem to help; the emotional brain doesn’t speak Rationalese.

The authors of UtEB claim to have found a therapy-based method that works, which goes like this:

First, they tease out the exact predictive model and emotional memory behind the symptom (in Richard’s case, the narrative where his father talked too much and ended up universally hated, and so if Richard talks at all, he too will be universally hated). Then they try to get this as far into conscious awareness as possible (or, if you prefer, have consciousness dig as deep into the emotional schema as possible). They call this “the pro-symptom position” – giving the symptom as much room as possible to state its case without rejecting it. So for example, Richard’s therapist tried to get Richard to explain his unconscious pro-symptom reasoning as convincingly as possible: “My father was really into talking, and everybody hated him. This proves that if I speak up at work, people will hate me too.” She even asked Richard to put this statement on an index card, review it every day, and bask in its compellingness. She asked Richard to imagine getting up to speak, and feeling exactly how anxious it made him, while reviewing to himself that the anxiety felt justified given what happened with his father. The goal was to establish a wide, well-trod road from consciousness to the emotional memory.

Next, they try to find a lived and felt experience that contradicts the model. Again, Rationalese doesn’t work; the emotional brain will just ignore it. But it will listen to experiences. For Richard, this was a time when he was at a meeting, had a great idea, but didn’t speak up. A coworker had the same idea, mentioned it, and everyone agreed it was great, and congratulated the other person for having such an amazing idea that would transform their business. Again, there’s this same process of trying to get as much in that moment as possible, bring the relevant feelings back again and again, create as wide and smooth a road from consciousness to the experience as possible.

Finally, the therapist activates the disruptive emotional schema, and before it can reconsolidate, smashes it into the new experience. So Richard’s therapist makes use of the big wide road Richard built that let him fully experience his fear of speaking up, and asks Richard to get into that frame of mind (activate the fear-of-speaking schema). Then she asks him, while keeping the fear-of-speaking schema in mind, to remember the contradictory experience (coworker speaks up and is praised). Then the therapist vividly describes the juxtaposition while Richard tries to hold both in his mind at once.

And then Richard was instantly cured, and never had any problems speaking up at work again. His coworkers all applauded, and became psychotherapists that very day. An eagle named “Psychodynamic Approach” flew into the clinic and perched atop the APA logo and shed a single tear. Coherence Therapy: Practice Manual And Training Guide was read several times, and God Himself showed up and enacted PsyD prescribing across the country. All the cognitive-behavioralists died of schizophrenia and were thrown in the lake of fire for all eternity.

This is, after all, a therapy book.

II.

I like UtEB because it reframes historical/purposeful accounts of symptoms as aspects of a predictive model. We already know the brain has an unconscious predictive model that it uses to figure out how to respond to various situations and which actions have which consequences. In retrospect, this framing perfectly fits the idea of traumatic experiences having outsized effects. Tack on a bit about how the model is more easily updated in childhood (because you’ve seen fewer other things, so your priors are weaker), and you’ve gone a lot of the way to traditional models of therapy.

But I also like it because it helps me think about the idea of separation/noncoherence in the brain. Richard had his schema about how speaking up makes people hate you. He also had lots of evidence that this wasn’t true, both rationally (his understanding that his symptoms were counterproductive) and experientially (his story about a coworker proposing an idea and being accepted). But the evidence failed to naturally propagate; it didn’t connect to the schema that it should have updated. Only after the therapist forced the connection did the information go through. Again, all of this should have been obvious – of course evidence doesn’t propagate through the brain, I was writing posts ten years ago about how even a person who knows ghosts don’t exist will be afraid to stay in an old supposedly-haunted mansion at night with the lights off. But UtEB’s framework helps snap some of this into place.

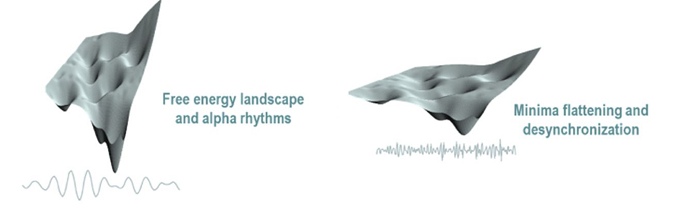

UtEB’s brain is a mountainous landscape, with fertile valleys separated by towering peaks. Some memories (or pieces of your predictive model, or whatever) live in each valley. But they can’t talk to each other. The passes are narrow and treacherous. They go on believing their own thing, unconstrained by conclusions reached elsewhere.

Consciousness is a capital city on a wide plain. When it needs the information stored in a particular valley, it sends messengers over the passes. These messengers are good enough, but they carry letters, not weighty tomes. Their bandwidth is atrocious; often they can only convey what the valley-dwellers think, and not why. And if a valley gets something wrong, lapses into heresy, as often as not the messengers can’t bring the kind of information that might change their mind.

Links between the capital and the valleys may be tenuous, but valley-to-valley trade is almost non-existent. You can have two valleys full of people working on the same problem, for years, and they will basically never talk.

Sometimes, when it’s very important, the king can order a road built. The passes get cleared out, high-bandwidth communication to a particular valley becomes possible. If he does this to two valleys at once, then they may even be able to share notes directly, each passing through the capital to get to each other. But it isn’t the norm. You have to really be trying.

This ended out a little more flowery than I expected, but I didn’t start thinking this way because it was poetic. I started thinking this way because of this:

Moving back a step: the paper is trying to explain what psychedelics do to the brain. It theorizes that they weaken high-level priors (in this case, you can think of these as the tendency to fit everything to an existing narrative), allowing things to be seen more as they are:

A corollary of relaxing high-level priors or beliefs under psychedelics is that ascending prediction errors from lower levels of the system (that are ordinarily unable to update beliefs due to the top-down suppressive influence of heavily-weighted priors) can find freer register in conscious experience, by reaching and impressing on higher levels of the hierarchy. In this work, we propose that this straightforward model can account for the full breadth of subjective phenomena associated with the psychedelic experience.

These ascending prediction errors (ie noticing that you’re wrong about something) can then correct the high-level priors (ie change the narratives you tell about your life):

The ideal result of the process of belief relaxation and revision is a recalibration of the relevant beliefs so that they may better align or harmonize with other levels of the system and with bottom-up information—whether originating from within (e.g., via lower-level intrinsic systems and related interoception) or, at lower doses, outside the individual (i.e., via sensory input or extroception). Such functional harmony or realignment may look like a system better able to guide thought and behavior in an open, unguarded way (Watts et al., 2017; Carhart-Harris et al., 2018b).

This makes psychedelics a potent tool for psychotherapy:

Consistent with the model presented in this work, overweighted high-level priors can be all consuming, exerting excessive influence throughout the mind and brain’s (deep) hierarchy. The negative cognitive bias in depression is a good example of this (Beck, 1972), as are fixed delusions in psychosis (Sterzer et al., 2018).25 In this paper, we propose that psychedelics can be therapeutically effective, precisely because they target the high levels of the brain’s functional hierarchy, primarily affecting the precision weighting of high-level priors or beliefs. More specifically, we propose that psychedelics dose-dependently relax the precision weighting of high-level priors (instantiated by high-level cortex), and in so doing, open them up to an upsurge of previously suppressed bottom-up signaling (e.g., stemming from limbic circuitry). We further propose that this sensitization of high-level priors means that more information can impress on them, potentially inspiring shifts in perspective, felt as insight. One might ask whether relaxation followed by revision of high-level priors or beliefs via psychedelic therapy is easy to see with functional (and anatomic) brain imaging. We presume that it must be detectable, if the right questions are asked in the right way.

Am I imagining this, or are Friston + Carhart-Harris and Unlocking The Emotional Brain getting at the same thing?

Both start with a piece of a predictive model (= high-level prior) telling you something that doesn’t fit the current situation. Both also assume you have enough evidence to convince a rational person that the high-level prior is wrong, or doesn’t apply. But you don’t automatically smash the prior and the evidence together and perform an update. In UtEB‘s model, the update doesn’t happen until you forge conscious links to both pieces of information and try to hold them in consciousness at the same time. In F+CH’s model, the update doesn’t happen until you take psychedelics which make the high-level prior lose some of its convincingness. UtEB is trying to laboriously build roads through mountains; F+CH are trying to cast a magic spell that makes the mountains temporarily vanish. Either way, you get communication between areas that couldn’t communicate before.

III.

Why would mental mountains exist? If we keep trying to get rid of them, through therapy or psychedelics, or whatever, then why not just avoid them in the first place?

Maybe generalization is just hard (thanks to MC for this idea). Suppose Goofus is mean to you. You learn Goofus is mean; if this is your first social experience, maybe you also learn that the world is mean and people have it out for you. Then one day you meet Gallant, who is nice to you. Hopefully the system generalizes to “Gallant is nice, Goofus is still mean, people in general can go either way”.

But suppose one time Gallant is just having a terrible day, and curses at you, and that time he happens to be wearing a red shirt. You don’t want to overfit and conclude “Gallant wearing a red shirt is mean, Gallant wearing a blue shirt is nice”. You want to conclude “Gallant is generally nice, but sometimes slips and is mean.”

But any algorithm that gets too good at resisting the temptation to separate out red-shirt-Gallant and blue-shirt-Gallant risks falling into the opposite failure mode where it doesn’t separate out Gallant and Goofus. It would just average them out, and conclude that people (including both Goofus and Gallant) are medium-niceness.

And suppose Gallant has brown eyes, and Goofus green eyes. You don’t want your algorithm to overgeneralize to “all brown-eyed people are nice, and all green-eyed people are mean”. But suppose the Huns attack you. You do want to generalize to “All Huns are dangerous, even though I can keep treating non-Huns as generally safe”. And you want to do this as quickly as possible, definitely before you meet any more Huns. And the quicker you are to generalize about Huns, the more likely you are to attribute false significance to Gallant’s eye color.

The end result is a predictive model which is a giant mess, made up of constant “This space here generalizes from this example, except this subregion, which generalizes from this other example, except over here, where it doesn’t, and definitely don’t ever try to apply any of those examples over here.” Somehow this all works shockingly well. For example, I spent a few years in Japan, and developed a good model for how to behave in Japanese culture. When I came back to the United States, I effortlessly dropped all of that and went back to having America-appropriate predictions and reflexive actions (except for an embarrassing habit of bowing whenever someone hands me an object, which I still haven’t totally eradicated).

In this model, mental mountains are just the context-dependence that tells me not to use my Japanese predictive model in America, and which prevents evidence that makes me update my Japanese model (like “I notice subways are always on time”) from contaminating my American model as well. Or which prevent things I learn about Gallant (like “always trust him”) from also contaminating my model of Goofus.

There’s actually a real-world equivalent of the “red-shirt-Gallant is bad, blue-shirt-Gallant is good” failure mode. It’s called “splitting”, and you can find it in any psychology textbook. Wikipedia defines it as “the failure in a person’s thinking to bring together the dichotomy of both positive and negative qualities of the self and others into a cohesive, realistic whole.”

In the classic example, a patient is in a mental hospital. He likes his doctor. He praises the doctor to all the other patients, says he’s going to nominate her for an award when he gets out.

Then the doctor offends the patient in some way – maybe refuses one of his requests. All of a sudden, the doctor is abusive, worse than Hitler, worse than Mengele. When he gets out he will report her to the authorities and sue her for everything she owns.

Then the doctor does something right, and it’s back to praise and love again.

The patient has failed to integrate his judgments about the doctor into a coherent whole, “doctor who sometimes does good things but other times does bad things”. It’s as if there’s two predictive models, one of Good Doctor and one of Bad Doctor, and even though both of them refer to the same real-world person, the patient can only use one at a time.

Splitting is most common in borderline personality disorder. The DSM criteria for borderline includes splitting (there defined as “a pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation”). They also include things like “markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of self”, and “affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood”, which seem relevant here too.

Some therapists view borderline as a disorder of integration. Nobody is great at having all their different schemas talk to each other, but borderlines are atrocious at it. Their mountains are so high that even different thoughts about the same doctor can’t necessarily talk to each other and coordinate on a coherent position. The capital only has enough messengers to talk to one valley at a time. If tribesmen from the Anger Valley are advising the capital today, the patient becomes truly angry, a kind of anger that utterly refuses to listen to any counterevidence, an anger pure beyond your imagination. If they are happy, they are purely happy, and so on.

About 70% of people diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder (previously known as multiple personality disorder) have borderline personality disorder. The numbers are so high that some researchers are not even convinced that these are two different conditions; maybe DID is just one manifestation of borderline, or especially severe borderline. Considering borderline as a failure of integration, this makes sense; DID is total failure of integration. People in the furthest mountain valleys, frustrated by inability to communicate meaningfully with the capital, secede and set up their own alternative provincial government, pulling nearby valleys into their new coalition. I don’t want to overemphasize this; most popular perceptions of DID are overblown, and at least some cases seem to be at least partly iatrogenic. But if you are bad enough at integrating yourself, it seems to be the sort of thing that can happen.

In his review, Kaj relates this to Internal Family Systems, a weird form of therapy where you imagine your feelings as people/entities and have discussions with them. I’ve always been skeptical of this, because feelings are not, in fact, people/entities, and it’s unclear why you should expect them to answer you when you ask them questions. And in my attempts to self-test the therapy, indeed nobody responded to my questions and I was left feeling kind of silly. But Kaj says:

As many readers know, I have been writing a sequence of posts on multi-agent models of mind. In Building up to an Internal Family Systems model, I suggested that the human mind might contain something like subagents which try to ensure that past catastrophes do not repeat. In subagents, coherence, and akrasia in humans, I suggested that behaviors such as procrastination, indecision, and seemingly inconsistent behavior result from different subagents having disagreements over what to do.

As I already mentioned, my post on integrating disagreeing subagents took the model in the direction of interpreting disagreeing subagents as conflicting beliefs or models within a person’s brain. Subagents, trauma and rationality further suggested that the appearance of drastically different personalities within a single person might result from unintegrated memory networks, which resist integration due to various traumatic experiences.

This post has discussed UtEB’s model of conflicting emotional schemas in a way which further equates “subagents” with beliefs – in this case, the various schemas seem closely related to what e.g. Internal Family Systems calls “parts”. In many situations, it is probably fair to say that this is what subagents are.

This is a model I can get behind. My guess is that in different people, the degree to which mental mountains form a barrier will cause the disconnectedness of valleys to manifest as anything from “multiple personalities”, to IFS-findable “subagents”, to UtEB-style psychiatric symptoms, to “ordinary” beliefs that don’t cause overt problems but might not be very consistent with each other.

IV.

This last category forms the crucial problem of rationality.

One can imagine an alien species whose ability to find truth was a simple function of their education and IQ. Everyone who knows the right facts about the economy and is smart enough to put them together will agree on economic policy.

But we don’t work that way. Smart, well-educated people believe all kinds of things, even when they should know better. We call these people biased, a catch-all term meaning something that prevents them from having true beliefs they ought to be able to figure out. I believe most people who don’t believe in anthropogenic climate change are probably biased. Many of them are very smart. Many of them have read a lot on the subject (empirically, reading more about climate change will usually just make everyone more convinced of their current position, whatever it is). Many of them have enough evidence that they should know better. But they don’t.

(again, this is my opinion, sorry to those of you I’m offending. I’m sure you think the same of me. Please bear with me for the space of this example.)

Compare this to Richard, the example patient mentioned above. Richard had enough evidence to realize that companies don’t hate everyone who speaks up at meetings. But he still felt, on a deep level, like speaking up at meetings would get him in trouble. The evidence failed to connect to the emotional schema, the part of him that made the real decisions. Is this the same problem as the global warming case? Where there’s evidence, but it doesn’t connect to people’s real feelings?

(maybe not: Richard might be able to say “I know people won’t hate me for speaking, but for some reason I can’t make myself speak”, whereas I’ve never heard someone say “I know climate change is real, but for some reason I can’t make myself vote to prevent it.” I’m not sure how seriously to take this discrepancy.)

In Crisis of Faith, Eliezer Yudkowsky writes:

Many in this world retain beliefs whose flaws a ten-year-old could point out, if that ten-year-old were hearing the beliefs for the first time. These are not subtle errors we’re talking about. They would be child’s play for an unattached mind to relinquish, if the skepticism of a ten-year-old were applied without evasion…we change our minds less often than we think.

This should scare you down to the marrow of your bones. It means you can be a world-class scientist and conversant with Bayesian mathematics and still fail to reject a belief whose absurdity a fresh-eyed ten-year-old could see. It shows the invincible defensive position which a belief can create for itself, if it has long festered in your mind.

What does it take to defeat an error that has built itself a fortress?

He goes on to describe how hard this is, to discuss the “convulsive, wrenching effort to be rational” that he thinks this requires, the “all-out [war] against yourself”. Some of the techniques he mentions explicitly come from psychotherapy, others seem to share a convergent evolution with it.

The authors of UtEB stress that all forms of therapy involve their process of reconsolidating emotional memories one way or another, whether they know it or not. Eliezer’s work on crisis of faith feels like an ad hoc form of epistemic therapy, one with a similar goal.

Here, too, there is a suggestive psychedelic connection. I can’t count how many stories I’ve heard along the lines of “I was in a bad relationship, I kept telling myself that it was okay and making excuses, and then I took LSD and realized that it obviously wasn’t, and got out.” Certainly many people change religions and politics after a psychedelic experience, though it’s hard to tell exactly what part of the psychedelic experience does this, and enough people end up believing various forms of woo that I hesitate to say it’s all about getting more rational beliefs. But just going off anecdote, this sometimes works.

Rationalists wasted years worrying about various named biases, like the conjunction fallacy or the planning fallacy. But most of the problems we really care about aren’t any of those. They’re more like whatever makes the global warming skeptic fail to connect with all the evidence for global warming.

If the model in Unlocking The Emotional Brain is accurate, it offers a starting point for understanding this kind of bias, and maybe for figuring out ways to counteract it.

The pictures of the energy landscapes remind me of a paper I was reading about how batch normalization helps artificial neural networks learn. Batch norm basically smooths out the gradient landscape, allowing the optimizer to easily figure out the direction to go instead of trying to follow valleys through to the minima. I’ll add a link to the paper if I remember in the morning; I just remember it was on the machine learning subreddit.

Couldn’t sleep so I found it: arxiv link. Turns out the graphics I was remembering were about the benefits of skip connections, not normalization. There are still some charts in the appendix that show normalization smoothing out the poss landscape, though, so I’ll keep this comment here.

I tend to be wary of these kind of analogies: the human brain has been compared to a mechanical watch, a hydraulic circuit, an electric circuit, a computer, a logical inference engine, a Bayesian network, and now of course an artificial neural network (ironically, since artificial neural networks were originally inspired by the brain). See the trend? The brain is always just like the latest fancy technology du jour.

Arguably, none of these analogies are completely misleading, they all have a grain of truth, but do they really help our understanding or are they just a source of false insight that suggests deep connections where there is nothing but superficial resemblance?

George Zarkadakis apparently traces the “mind as metaphor for most advanced technology” trend all the way back to “clay infused with a soul” biblical description. This is an analogy with the most advanced contemporary technology: the clay pot, which contains a fluid.

My mom (a therapist) and I have an inside joke about this, imagining a sort of stage-zero metaphor, “your brain is like a rock. Some days the rock is good, other days, not a good rock.” There’s more comedic than analytic mileage in this one, perhaps.

https://aeon.co/essays/your-brain-does-not-process-information-and-it-is-not-a-computer

To be fair, no mechanical watches or even computers (without a NN) have ever been able to do the tricks that modern NNs are capable of, such as successfully playing a new computer game just from the screen, without advance knowledge of its rules.

Yes, any new technology is better than the previous ones, at least at something.

Still, it’s complicated.

For instance, between the 50s and 80s the predominant psychological theories were based on congnitivism: the notion that the mind is structured similarly to a traditional, high-level software system, with files and databases, discrete arithmetic, formal grammars to generate and understand language and GOFAI-style planning and inference. After all, this was the most advanced technology at the time, and it did in fact replicate some of the cognitive skills of humans. It turns out that it replicated some of these skills way better than human-level (try to beat a 70s era pocket calculator at doing multiplications or a floppy disk at storing data), but was crap at other skills.

When in the 80s-90s artificial neural networks first became interesting, psychology mostly abandoned congnitivism for connectionism, the notion that the mind is just the product of a big black-box neural network without much discernible internal structure, trained to maximize some sort of reward signal. Then artificial neural networks went into their AI winter, neuroscience started to find lots of specialized modules inside the brain and psychology began to move towards Bayesianism. Then ANNs came back in the 2010s and are now the dominant AI paradigm, neuroscience and classical psychology stalled and went into replication crisis, so connectionism is coming back, now with fancy deep learning terminology such as “energy landscapes”.

ANNs do in fact reproduce some human cognitive skills, in some cases better than humans, still they are crap at other skills. This is why I’m wary of such analogies.

> the notion that the mind is just the product of a big black-box neural network without much discernible internal structure, trained to maximize some sort of reward signal.

Apart from anything else, this notion has one big advantage: it is much easier to imagine how it could gradually evolve from something extremely primitive — as opposed to, e.g., a computer-like brain with a rigid structure and boundaries between RAM and the processor. For this reason alone, cognitivism and connectionism, to me, are not even comparable in their level of plausibility. They are like top-to-bottom and bottom-to-top descriptions of something — but since we know that this something did in fact grow from bottom to top, the top-to-bottom description is of very limited interest.

Many organs and systems of the body are made of parts with clearly identifiable functions. E.g. the eye is structured like a camera, with a sensor (retina), a biconvex lens, a diaphragm (iris) and various muscles to change orientation and focus. The circulatory system has pipes (arteries and veins), valves, a pump (heart), gas exchangers (lungs), filters (kidneys), and so on. It was not prima facie implausible that the human brain was also structured similarly.

Wariness of analogies is justified.

At the same time, technology iterates towards higher levels of capacity. AI development isn’t progressing ultra-fast, but it is manifestly progressing; whatever it means to ‘think,’ we are getting closer to machines that think.

Therefore, it is increasingly likely that we will encounter technological discoveries that are at least vaguely related to how the brain really works. No amount of “pot full of liquid” metaphors get you very far understanding the brain, because it’s just too simplistic. But a machine that has components explicitly modeled after the kind of things we know the brain does? That may very well provide us with some insights.

Trying to say “the brain is just like [piece of tech]” is obviously fallacious. But there are still things we may learn from analogy to pieces of tech.

While reading your last sentence, I was reminded of how the atom has been compared to a ball, a plum pudding, a planet with moons etc. – all of these models are useful in some way or another, and they did help my understanding of different parts of basic chemistry.

Sorry for responding to the part of your post you most likely don’t want to be responded to all that much, but:

really doesn’t match my experience. About half of the skeptics I’ve discussed this hold the following belief:

“Climate change appears to indeed be happening. The degree to which it is threatening is likely overblown due to the current political climate(heh). I am not yet fully convinced it is anthropogenic in nature, as (ref.1), (ref.2) and (ref.3). I know these are contested and there are many other studies contradicting these. As I am not a climatologist, I consider the issue to be “currently unsolved”. When politics is involved, I am not eager to accept the overall consensus if there is even a single piece of evidence that does not appear to be fabricated that challenges it. In case climate change is indeed anthropogenic, I am still not convinced it can be countered by policing the first world rather than currently industrializing nations. And even if we are at fault, whatever the effects of it might be, they cannot be worse than a one world government led by the current crop of globalist neoliberal nanny state wanna be dictators we have pushing for it.”

Notice how It’s a position starting with an open mind in regards to the factual, increasingly biased as the topic becomes more political (as is always the case) and then we find a series of fallbacks all the way down to a complete rejection of governmental (perceived) overreach.

It’s possible that when you are discussing the issue with a skeptic the issue becomes political (in their mind) from the get go, skipping entirely the lush meadows of factology. I am unsure why would this happen, as you always treat the Other tribe with respect. Could be something specific to the american climate skeptics.

Oh! About this :

I unknowingly and accidentally applied this form of therapy on myself between ages 16 and probably 19-ish. It got pretty involved over time, with a sort of an inner council of four personified approaches to life discussing among themselves the best course of action, both long and short term. The terms of the discussion were not always civil.

Its unclear to what degree this influenced my subsequent descent into stuff that is still an issue more than ten years later. But it was fun at the time, so there’s that. 6/10 therapy, wouldn’t recommend to everybody, especially if they are already somewhat dissociative as I seem to have been.

Anything that dictates how people should be compelled to act is political, climate change becomes a political issue when any kind of legislative measure is proposed.

The issue is both factual and political. They can be discussed separately.

If one decides that the political side of the issue is important enough that the factual doesn’t matter, that’s one thing. If he decides that the political is so important that he must insist that the facts supporting the other side are wrong (when they may not be), then he is setting himself for failure, as his position is built on shaky foundation easily exploited.

If one’s rejection of anti-climate-change legislation is deeply political, but masked as the position that climate change isn’t actually happening, the opposing side can present more evidence until they weaken his publicly held position to the point of ridicule. If the opposing side has a strong grip on the academia and/or the media, evidence doesn’t even need to be particularly strong. This will leave him at a very weak position later on the table when the issue of legislation is forced.

If one however rejects anti-climate-change legislation entirely on political grounds, this gives certain freedoms. No matter how many tear jerking videos of the displaced inhabitants of an island in the pacific ocean he is forced to endure, he does not have to concede any ground politically, at least until a legislation is proposed that takes into consideration his highly specific requirements in regards to governmental overreach.

Overall I feel the “climate-change-denial” side were defeated politically the moment they allowed themselves to be manipulated into insisting publicly that climate change isn’t happening. Which seems somewhat typical for the political right over the last half a century or so.

They can be discussed separately – but they won’t be, because arguments are soldiers.

If you want this to be discussed separately, you have to create a space that is deeply, convincingly on board with rank hypocrisy. To the level of “I think climate change is happening, but I’ll still vote as if it wasn’t, and I don’t want to talk about why.” And nothing even slightly bad or embarassing has to happen to this person. Anything less than that, you’ll get incentive to adjust your factual beliefs to support your political ones.

I don’t think there’s lack of different opinions on the spectrum – climate change isn’t real, is real but not anthropogenic, is real but any legislation that isn’t focusing on destroying China is meaningless, is real but not worth legislating – you are just mostly presented with strawmen by media and stupid people who parrot it mistaking it for official party line.

I agree with you. I think that Republicans are ultimately setting themselves up for failure and ridicule by failing to acknowledge the reality of climate change, even while mass migration and environmental apocalypse occurs all around them. This should be deeply frightening for them, since whenever a disaster occurs, the first thought in the public consciousness is “Whom should we blame for this?” Do Republicans really want to be the fall guys who take the blame for the end of the world?

A wiser strategy would be to say “Look, climate change is happening, but we disagree on the best approach to combat it. Democrats keep saying that we should go green, but any rationalist who has studied incentives problems knows that it is useless for us to go all in on the environment when China and lots of third world countries are continuing to pollute and build coal plants. Why should the United States spearhead the immense financial burden of stopping climate change when we are the nation that will be least impacted? If these other nations – which will likely be totally obliterated by climate change – don’t even care enough about their own survival to adopt green technology, then why should we subsidize their existence when we could instead spend that money to improve our own climate change resilience?”

To this, Democrats will predictably answer “Because mass migration means that their problems will become our problems. It’s easy to say that their stupidity will only impact them, but in reality we’re talking about millions of immigrants sweeping across the border once their nations start collapsing.”

And the Republican answer can simply be “Hey, their problems don’t have to be our problems. Only reason they would be is if you guys are too chickenshit to play hardball. We have the technology to make the border completely impassible if we want it to be. Deploying landmines and weaponized AI at the border can drop immigration to literally zero. These civilizations chose not to cooperate and pay their fair share when it comes to stopping climate change, so they made their bed and they can lie in it. Play stupid games, win stupid prizes. Best of all, since the citizens of these nations are now aware that there will be no mercy for them if their own stupidity and stubbornness causes their nations to collapse, fear will make them highly incentivized to change their selfish ways and start adopting green technology quicker, because now its their own lives and the lives of their children on the line.”

You might say that this is an unrealistic position for Republicans to take, because it sounds villainous and unsympathetic. And it is… at least in the current year. But culture changes rapidly depending on how desperate your situation is. In a world full of abundance (like the one we have now) that kind of uncaring “survival at all costs” mentality sounds very unsympathetic to your average voter. But in ten years or so, after a few European countries have completely collapsed due to mass migration, people are going to be a lot more scared and desperate, and they will be willing to allow their governments to take much more drastic measures if it preserves their own quality of life. If Republicans start using negative talking points about these other societies now, pointing out how we subsidize them to be more green while they waste and embezzle the money on internal corruption (which a is completely fair accusation in many cases) then by the time the world is at crisis point, the game plan of sealing the borders and letting the “uncivilized barbarians” drown is going to look pretty appealing to your average voter. The logic going through their heads is “Why should we endanger our own chances at survival so that you can live? You brought this upon yourselves by being selfish and failing to cooperate when you had the chance.”

Look at how quickly European culture has changed in the past few years. When the refugee crisis started, Germany had a policy of Willkommenskultur. But as soon as it turned out that the refugees were not the well-behaved people that delusional idealists expected them to be, that attitude changed real quick. Populism surged, and now many European countries are actively hostile to migrants. And this is only the beginning! Imagine how hostile they’re going to get once one of these lovey-dovey open-borders countries totally collapses due to mass migration. Shit will hit the fan with a quickness, and anybody who has a credible game plan to stop civilization from falling into chaos (whether that’s a politician looking to gain power, or an entrepreneurial merchant selling weaponized AI or other useful technologies) will most likely end up in high demand.

Much like the “global warming isn’t happening” strategy, this is vulnerable to being mugged by reality. For example, when China starts investing in solar power harder than any other nation on the planet and building scads of nuclear reactors.

At some point it becomes apparent that China is taking the problem seriously, or at any rate more seriously than the Republican Party.

This, too, is a strategy vulnerable to being mugged by reality if the expected collapses don’t materialize. Given the level of sensationalism that has so far been required to keep up the narrative of “European nations are on the brink of collapse because too many migrants,” this may be difficult.

The other problem with the suggested argument is that it basically boils down to “we should be prepared to machine-gun millions of people at our borders rather than just, y’know, build solar panels and live in smaller apartments closer to the city center and things.”

Inasmuch as this is a hard sell, it’s a hard sell. If it becomes an easy sell, you’re going to have an entirely different set of problems. Starting with “what if a government accustomed to ‘not being squeamish’ about machine-gunning millions of otherwise harmless people who want to enter the country stops ‘being squeamish’ about its treatment of people inside the country?”

The mentality of machine-gunning climate refugees for trying to cross the border is not far removed from the mentality of deporting one’s own racial or class “undesirables.”

You have a very unrealistic sense of confidence in China’s willingness and ability to address climate change. My sense is that they pay lip service to the problem and then go right ahead and build hundreds of new coal plants. Perhaps you should pay less attention to what China is saying and more attention to what they are doing.

You say this, and yet you have the balls to talk to me about being “mugged by reality?” Your view of reality itself (certainly, insofar as it applies to China) seems completely at odds with the evidence. In Beijing, the air is so polluted that I could stare directly at the sun at midday, and yet China is still going full speed ahead on coal. In their capital city, the tap water is undrinkable and makes people violently ill. Nobody cares. China doesn’t care about the environment, nor will they until it causes a revolution. Their ruling class is primarily made up of very short-term thinkers who lack the ability to resolve cooperation problems.

Again, I don’t think you’re living in the same reality as the rest of us. From my perspective, what has been far more difficult is maintaining the fictional narrative that everything in the EU is fine. Our current US president is talking about not defending NATO allies while German soldiers are training with sticks because they don’t have enough guns. Generally speaking, when you are a country with no effective military to speak of and your main ally is talking about pulling out of the alliance and leaving you to your own devices, your situation is somewhere between “totally fucked” and “up shit creek without a paddle.” The EU most definitely is on the brink of collapse, and I’m not sure how you can interpret the data any other way. When the government is unable to maintain order that’s a symptom of civilizational collapse. When you are unable to police areas within your own country because law enforcement has effectively ceded control to organized gangs, this too is a symptom of civilizational collapse. Anybody with common sense can see it for what it is, regardless of how the media may try to spin it. The collapse of Rome started with a refugee crisis also.

That’s not a problem at all. People only get squeamish about death when they have to deliver it up close and person. When it’s a drone delivering death remotely, Americans don’t care much. The further your average voter is from doing the dirty work themselves, and the easier you make it for them, the less reluctant they will be to pull the trigger. When the message is as easy as “Hey, push this button and killer AI will patrol the border for you. They will humanely push people out and only gun down people who resist (and let’s be honest, those people are kind of asking for it)” then most voters will be very inclined to agree, particularly when they have just seen European nations collapse for being too compassionate.

Do you even pay attention to the news? Our government has never been squeamish about its treatment of people inside the country. They’re only squeamish about being discovered. The idea of pushing a button and having unstoppable emotionless AI take care of the border control problem is far nicer and more sympathetic than some of the dark extralegal actions that our government has already committed.

I’m sorry if this line of thinking bothers you. I’m just saying that climate change is a multipolar coordination problem, and trying to solve any sort of multipolar coordination problem without leveraging fear as a tool against defectors is completely impossible. This truth may be bitter and hard to swallow, but it is a fact of life. That means that if you seriously want to resolve the problem (instead of just virtue-signalling intent to resolve the problem) then you have to accept fear as one of the tools in your mental toolbox. The progressive refusal to leverage fear against foreign countries who fail to uphold their climate change commitments is the reason that progressives have failed so utterly at combating climate change. They are trying to fix a complex problem with an inadequate set of tools.

For the record, your characterization of climate skeptics is one of the most accurate descriptions of my point of view on the matter that I have ever seen someone write down. Congratulations for being the first person to engage with people like myself in good faith. That last sentence might sound sarcastic but I mean it sincerely

My view as well, regarding climate science. Anthropogenic, but slow, not that bad, not all bad, and unlikely that the place to start is first world countries now. And sure as hell not with plastic straws. But I’m guessing that’s not what Scott is talking about – there most likely exists a minority that is just rejecting anthropogenic climate change outright. Maybe not in our bubbles – probably not in our bubbles – but it’s there. For another so-controversial-it’s-fun example – socialism (hey, Scott started!). Stuff like rent control. For another – libertarians who completely ignore commons problems. The extremes of any position are pretty obviously wrong, and yet there are people that are arguing for them (assumingly) in good faith.

Regarding Inner Voices Therapy, and the main point of the article, probably my main mental health (? mental optimization?) issue is that the inner actors don’t have voices. I know they’re there, I understand them intellectually (Minsky’s Society of Mind is a damn good book btw), it’s pretty obvious they exist and are quite opinionated but… they don’t have a voice in my inner dialogue. Hell, I don’t have an inner dialogue. Any hint on how I could create one would probably be most useful for me long term.

My experience with people who do not believe in climate change outside of the Rationalism sphere (non-Rationalists being a much much larger group than Rationalists, I do not think this is some small minority), is that they barely have a coherent belief regarding AGW at all, and are mostly just repeating whatever talking points they last saw in a meme or a PragerU video or something. They’ll at once claim that 1) all those temperature graphs are faked via massive international conspiracy to take your hard-earned money, so there’s no warming, 2) there is warming but it’s fine because the climate has always been changing, 3) scientists all lied about global cooling in the 70s so they’re obviously just lying again, there’s no warming, 4) it’s impossible for 400ppm atmospheric CO2 to warm the planet because that feels like a really small number, 5) there was a cold snap last week, checkmate liberals

etc.

This is the level of intellectual engagement I’m used to irl. They seem to sincerely believe it, it’s just their standard for argumentation is ridiculously low.

(And fyi, banning plastic straws is about plastic pollution in oceans and waterways, not global warming, though I’m sure there are some foolish environmentalists out there who have conflated those two issues as well)

This is needlessly and suspiciously specific. Your characterization is generally true of people who hold any strong belief re climate change, regardless of whether that belief is “climate change is certainly real and dangerous” or “climate change is certainly not real”. They just use different memes and videos for source material.

One of these groups will coincidentally hold beliefs that are closest to objective reality, but that doesn’t make them smarter or more rational than the other. And really, they’re all fairly smart and rational about this, because outside the freakishly small Rationalsphere, there is almost no benefit to holding climatological beliefs that are objectively accurate and a high cost to holding climatological beliefs discordant with those of your social circle.

I see the point you’re making but I think it’s somewhat of a false equivalence.

The average AGW-believer has been hearing for the last 30 years that global warming is real and serious and all the relevant experts and authority figures are concerned about it. So they basically just defer to the consensus/experts, because hey, those people at NASA/NOAA etc probably know what they’re talking about.

This is a fairly reasonable heuristic overall.

Meanwhile, the average AGW non-believer rejects 30 years of scientific consensus on the basis that either 1) those experts are fools who know less about their topic of study than me, A Random Guy, or 2) those experts are all liars/frauds/biased and acting nefariously to gain more power and money.

Both groups have very little knowledge of the details of global warming, and have little incentive to care about accuracy, as you point out. If you asked them about specific details, they’d both gets lots wrong since they get their information from memes and other bad media. But would you agree that the first heuristic (“defer to expert consensus”) is more reasonable than whatever heuristics are driving the second set of beliefs (“predictions of catastrophe are almost always wrong”, “anything the left wing government gets behind is probably bad”, “I trust my own intuitions over what some pencil-pushing urban elites have to say” as a few potential examples)?

@Eigengrau

The average AGW-believer is in fact not listening to NASA/NOAA scientists, nor do they read the IPCC reports. Instead, they tend to get their information from people who tend to distort the science for various reasons.

Ironically, the falsehood that mainstream consensus = expert consensus, is part of the distortion.

Thirty years, did you say?

Climate catastrophism has a terrible track record. And the people putting their fingers on the temperature scale aren’t particularly subtle about it any more (e.g. “pausebusting”). So I think the “so-called experts are liars and frauds” hypothesis is not something which can be rejected out of hand.

As Aapje points out, they do no such thing. And I’d wager that if you ask three random AGW-believers, two of them wouldn’t even be able to tell you what “NOAA” stands for without a hint. They defer to non-scientist middlemen like Al Gore and Bill Nye and I guess now Greta Thunberg, who tell them that the Consensus Of Smart Honest Science Guys is X and that all the Not-X believers are liars being paid by Big Evil. And then they feel good about being on the side of the smart honest people, and they find themselves surrounded by friends and family who tell them how smart they are to believe X.

Which is pretty much exactly what the average AGW-denier does.

@TheNybbler

Are you misinterpreting “A senior U.N. environmental official says entire nations could be wiped off the face of the Earth by rising sea levels if the global warming trend is not reversed by the year 2000.”

as

“A senior U.N. environmental official says entire nations could be wiped off the face of the Earth by the year 2000 by rising sea levels if the global warming trend is not reversed.”

?

Because otherwise his predictions are not unreasonable, even though the article represents only the doomiest and gloomiest end of the forecasting.

Trends weren’t reversed by the year 2000. It’s now the year 2019. The only nation mentioned that was wiped off the face of the Earth is the one they said would do best — the USSR. Admittedly, Russia has indeed had a bumper wheat crop since then, but the US and Canadian wheat regions have not become dust bowls. Even Bangladesh, though it has indeed experienced flooding (and predicting that is like predicting the sun will rise in the East), is still around.

@John Schilling

Not sure where we actually disagree here. Yes, AGW-believers mostly get their info from scientific middlemen. And yes, they have little knowledge of the actual details. But the scientific middlemen lean really heavily into appealing to expert consensus. Greta Thunberg’s whole bit is begging people to listen to scientists because she is only a child. So the appeal to AGW-believers is still very much “this is what the experts think”.

Anyways, this is getting way off topic now. My original point was that, in my experience, climate skeptics that reject AGW outright are not a minority of climate skeptics overall, as Radu suggested.

(Also, for the record, *I* didn’t know what NOAA stands for without looking it up. Something oceans something atmosphere?)

@Eigengrau

No, Thunberg’s bit is to accuse older people of failing children/future generations, demanding that older generations give up wealth.

—

In her UN speech, she claimed that: “People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction”

None of that is in the IPCC reports.

This depends completely on how you define skeptics. According to a YouGov survey, 15% of Americans believe that climate change either doesn’t happen or that it is not caused by humans. However, according to another poll, 62% of Americans believe that climate change is caused mostly by humans. So that makes for 38% of Americans who can be called skeptics by a definition of a skeptic as someone who rejects the idea that humans are mostly caused by humans. Yet the majority of them apparently don’t reject some AGW.

A survey also also found that 14% of Americans believe it is too late to do anything. You can call these people skeptics of the current approach to combat climate change.

Then you have people who object to specific solutions, like the idea that climate change can be fought without nuclear power, without gas, etc. These people can also be called skeptics by some definition.

@Eigengrau

Guess it’s time to link this post again.

Through the last decades climate scientists have been predicting anything from a new Ice Age to warming so extreme that the polar ice caps would completely melt. Anything from snow-free Britain to Britain with a Siberian climate. None of these catastrophic predictions turned out to be accurate.

Add all the scandals of scientists caught red handed fiddling with their data to achieve predetermined outcomes, or colluding to suppress the publication of papers presenting evidence contrary to their position, and you don’t really get a picture of trustworthiness.

It is kind of disingenuous to use the very large error bars associated with 1975-1980 climate modeling to discredit the much narrower error bars associated with 2015-2020 climate modeling.

Firstly, climate modeling is a computationally intensive field, and the multiple orders of magnitude in improvement of computer technology would have an obvious, predictable effect on the quality of the models.

Secondly, any model based on data tends to get better, not worse, a more data are added. We have 30-40 years more climate data now than we did at the dawn of the science, including entire categories of data that did not exist or were in their infancy then (e.g. satellite data), and a wealth of ‘deep history’ data (e.g. ice cores) that had not been collected in those days.

Thirdly, we have now had about two generations to evaluate and reject the most deeply flawed models of how climate would change. Several such models have indeed been rejected. This is no more ‘proof’ that the remaining models are flawed than the debunking of Piltdown Man ‘proves’ that australopithecus africanus never lived.

What the average AGW believer is believing is that the scientific community, on the whole, has gotten its shit together, and that while some of their best efforts at evidence-based climate prediction may be wrong, not all their efforts are wrong.

The much narrower error bars haven’t been tested. If your 1975-1980 models didn’t work, and your 1990 and 2001 models didn’t work, why should I believe your 2015-2020 models?

This is pretty typical for what dumb people (and there are many of those) believe when they doubt AGW. However, dumb people who support AGW aren’t much better. And there are also some smart people who doubt AGW.

> unlikely that the place to start is first world countries now

Whether you like it or not, first world countries are a place where most things start; if they don’t start there, they rarely stand a chance. So it’s not an issue of who pollutes more; it’s an issue of who will or will not be listened to.

I don’t really see your description of what the skeptic believes as matching the emotional/rational dissonance described in Scott’s post. It is more like “Climate change is real, but there are various caveats to that, as well as other reasons why we shouldn’t vote based on it even if it is real.” But both the emotional and the rational brain are saying this. What doesn’t seem to happen is people saying “Climate change is real, and I should vote accordingly, but I can’t bring myself to do so.”

This sounds a lot like “solution aversion“. The gist is that people are afraid of the proposed actions, and so express excessive skepticism toward the evidence that motivates those actions. Only when carefully pushed to do so will they reveal that their true objection is to the proposed solution rather than the evidence for the problem.

This is baffling to me, because the belief you describe is quite charitable and reasonable, but your equating it with Scott’s formulation is very much not. The people you describe might well say,

“I know climate change is real though probably not catastrophic, but for a very obvious reason reason I can’t make myself vote for things that probably do very little to prevent it and will be catastrophic in other ways”.

The bit where you do a hack edit like so,

“I know climate change is real

though but probably not catastrophic, but fora very obvious[some] reason I can’t make myself votefor things that probably do very littleto prevent itand will be catastrophic in other ways“, is fundamentally dishonest. Yes, the person hypothetically said those words in that order, but by editing out all the other important words, you invert a rational position into an irrational one and falsely attribute that irrationality to another. You shouldn’t do that, and you should feel bad about having done that.The problem arises when multiple different lines of potential solutions are all rejected, and then the skeptic proceeds to vote in a government that aggressively denies the existence of global warming and cuts funding for even studying how to solve the problem.

If actions reveal preferences, this is not suggestive of a preference for ‘rational, effective’ action to counter global warming. It suggests a strong preference for doing nothing and hoping things won’t be that bad.

What is the universe in which one can “vote to prevent climate change” in any sense other than symbolic? I challenge anyone to produce a shred of evidence that anyone’s vote will have any influence on global climate. To imagine that one’s vote in, say, the US, will slow the construction of coal-fired power plants in China and avert global climate catastrophe (if that is what you “believe in”), is a leap of faith undreamed of by the most devout religionist.

Even for domestic reductions in CO2 production, my newspaper is cycling between:

– X is an important solution for climate change

– X is untenable due to reasons

They unwittingly seem to be sending a message that it is rather hopeless.

I will note that if China really weren’t interested in addressing this problem they’d be doing a lot less with solar and nuclear.

And furthermore that, if nothing else, we’re probably not going to get meaningful efforts at geoengineering until politicians actually face the prospect of having to spend trillions on carbon emissions reduction.

Your argument generalizes to “democracy doesn’t work at all and you should never vote for any reason.” Do you agree with that generalized statement?

“Climate change appears to indeed be happening. The degree to which it is threatening is likely overblown due to the current political climate(heh). I am not yet fully convinced it is anthropogenic in nature, as (ref.1), (ref.2) and (ref.3). I know these are contested and there are many other studies contradicting these. As I am not a climatologist, I consider the issue to be “currently unsolved”. When politics is involved, I am not eager to accept the overall consensus if there is even a single piece of evidence that does not appear to be fabricated that challenges it. In case climate change is indeed anthropogenic, I am still not convinced it can be countered by policing the first world rather than currently industrializing nations. And even if we are at fault, whatever the effects of it might be, they cannot be worse than a one world government led by the current crop of globalist neoliberal nanny state wanna be dictators we have pushing for it.”

The error I see Scott making in the post is simpler: he started with “believe in anthropogenic climate change” and then switched to “vote to prevent it”. One can believe anthropogenic climate change is happening but still quite rationally refuse to vote for any of the schemes that have been proposed to prevent it–simply because you don’t think any of them will in fact prevent it. And that belief seems perfectly rational to me, since the key takeaway from all climate prediction anyone has done thus far is that nobody is very good at predicting future climate. Which in turn implies that nobody is very good at predicting the effects of interventions. With that set of beliefs, adaptation seems like a much better option than attempts at mitigation, particularly attempts at mitigation that are going to cost many trillions of dollars and require restructuring the entire global economy. The track record of humans at doing that without causing disaster is even worse than our track record of predicting future climate.

To get back on topic for the overall post: before one concludes that people are irrationally ignoring evidence, one should first be very, very clear about exactly what belief one is claiming there is evidence for. That means being very, very careful not to conflate beliefs that, while distinct, are often held together.

> Richard might be able to say “I know people won’t hate me for speaking, but for some reason I can’t make myself speak”

What Richard would likely say is “I know people won’t hate people like me for speaking, but for some reason they will still hate me personally for saying exactly the same thing”

What if he’s right? That there’s some difference, unnoticed by him and noticed (but not consciously or in a way able to be articulated) by others which results in him being hated for saying the same things others say.

His views may well be accurate, yes, potentially for the reasons you mention.

And if he’s right, successfully encouraging him to do the thing will only _reinforce_ his belief that he shouldn’t do it. And if he does it, comes back and reports that he did it and was hated for it, and the therapist says something idiotic like “Well you must have done it wrong” or “I didn’t mean _that way_”, now the therapist has a bloody nose and Richard has an assault charge.

I have a shelf full of books from the 70’s (Structure of Magic, Virginia Satir et al) with plenty of actionable things to enact to help get people over these issues.

Thing is, the theories they have behind them are all disproven or the techniques don’t match modern ethical considerations and so no one uses the techniques any more even though the methods work.

For instance, Richard could have had this issue sorted out simply by getting him deliberately be a complete tosser to other people for a bit in the way he personally dislikes. He’d find it isn’t so bad actually, his mental schema would update and then there’d be an integration naturally. Good luck getting that past the ethics committee and/or insurance agent.

Another way to do this is to generate another extreme feeling to counteract the anxiety which removes the feeling but leaves the behaviour as a choice.

Anyway…

The most interesting question is not why but how we hold different opinions at the same time. A decent working but unprovable theory is we use different sense memory to do so. i.e. our thinking about topic one is held in visual memory and our thinking about topic two is held in auditory memory and so they don’t interact (except if reality/therapy intercede).

Finally a totally random point about climate change. Most people think its real, a lot of people don’t want to change their behaviours because they won’t benefit personally – they also know that saying openly “I don’t care if your or even my own grandchildren live in an oven, I got mine. SUV’s are awesome and I’ll be long dead by the time the shit hits the fan” is a non starter and so instead they move upstream and deny the science.

“The most interesting question is not why but how we hold different opinions at the same time. A decent working but unprovable theory is we use different sense memory to do so. i.e. our thinking about topic one is held in visual memory and our thinking about topic two is held in auditory memory and so they don’t interact (except if reality/therapy intercede).”

I think this might be giving people too much credit. I think it’s the same phenomenon as Russell conjugation (“I am principled, you is obstinate, he is pig-headed”), and the thing where people hold different opinions on the same topic depending on what word you use for it (“Violent crime is very low and the media panics people about it unnecessarily…but gun violence is a national crisis”)

You can use the different modalities to get a different response reliably.

Richard in your example will have images of his father in mind with the anxious feeling attached but his auditory experience (internal auditory as well) will not be attached to those images or feeling.

We aren’t really talking about the pigheaded, we are talking about people who admit openly their emotional reactions are dumb, the reason they are seeking therapy in the first place but cannot change them.

Well, by putting together their split experiences, you can resolve their difficulties. However as I said before the ethics of it are far from in vogue because it means putting people in guaranteed distress for a possible (though highly likely) good outcome.

Are you talking about NLP without mentioning N-L-P so people don’t panic?

Pre NLP – the actual therapists like Satir who the NLP lot stole from.

How exactly does one accurately describe a society where muggings, burglaries, and petty vandalism have been declining since the 1980… But where random mass shootings by people with little or no prior criminal record, and who cannot plausibly hope to profit from their crime, have been rising during the same time period?

While gun violence is a subset of violent crime, the central example of “gun violence” as we now imagine it to be a threat is not a central example of “violent crime.”

It’s entirely possible to live in a society where violent crime (an aggregate of bare-knuckle attacks, knifepoint mugging, breaking and entering possibly, rapes, and other offenses) is on the decline. And yet to have a society where the central example of “gun violence” (Person A shoots Person B) is about as common as it ever was, or even more common.

Furthermore, an epidemic of mass shootings may present a national crisis of a very different sort than a generalized violent crime wave, one which requires entirely different solutions to address. It turned out that the best solutions to the 1970s and ’80s crime wave were “ban leaded gasoline and legalize abortion.” These solutions do not appear to be working to prevent rising levels of mass shootings.

One hopelessly besotted with a mass media optimized for entertaining fools. “If it bleeds, it leads” is an oversimplification, it has to be novel and bloody to be suitably enthralling infotainment. So, every few years, there’s a new moral panic chosen almost at random and without regard to the actual material harm involved. See e.g. the year of the shark.

Usually this causes no more than pointless terror because e.g. sharks don’t watch CNN and say “hey, yeah, biting tourists is the thing to do!”. Potential mass shooters, so, and so there’s positive feedback. That, plus increasing existential despair and not-giving-a-fuck, gets you the Year of the Mass Shooting.

Which, like the Year of the Shark, will last until the media gets bored of it or something bigger happens. But because of the positive feedback, it may take a bit longer this time.

In the same vein, I once knew someone deep into astrology and eventually came to realize they were just operating with different symbols. Where I would summarize a pattern as strident, self-assured etc. they would say ‘fire type’. And they would then derive predictions of social in-/compatibility with other types that were not too different from the predictions my symbol system would offer.

On a long-term, global scale I’m convinced the system that is open to change or revision is better and the one with specific, falsifiable claims is better, but locally the difference for day-to-day life is small and easily swamped by other factors.

Similarly, UtEB obviously would have some connection to other symbol systems and be prima facie plausible. It was created by humans after all, so it’s hardly surprising that it matches to some patterns observable in humans. And locally, it’s trivially true that it works for some people, just like talking about ‘fire types’ works in the sense of generating useful predictions or solutions for some people. However, the part that’s interesting to me is whether it creates specific, falsifiable claims (apparently no) and whether it can update (apparently no). So, how is it different from astrology?

Great question – I’d also ask “What can you do with this knowledge?”

With astrology you can get housewives to part with their small change, with UtEB the practical bit seems to be extracting a slightly larger amount from a smaller and harder to convince demographic.

As often occurs with “therapy books” – UtEB seems to be either just a re-write of a couple of 60’s/70’s classics with new terminology or a genuinely brand new arrival at existing knowledge.

What can you do?

However, the part that’s interesting to me is whether it creates specific, falsifiable claims (apparently no)

UtEB gives you a specific sequence of steps for achieving belief updating, as well as a general theory for why those steps work and what you can do to troubleshoot them if they don’t work. See my review (which Scott links to at the beginning of the post) for details.

I’ve personally found that they work very well, and that they also accurately describe several other self-therapy techniques that I’ve successfully used and which in retrospect feel like special cases of UtEB’s more general process.

Er… you can see right in the name that astrology is not primarily about coming up with new names for everyday concepts, but rather about connecting them with astronomical phenomena. That is the part that is bogus.

@Dacyn

I see your point, but consider:

(1) Astrologers work from a false premise (the stars influence …), but

(1a) part of that premise is just causally wrong, but empirically right for the wrong reasons. E.g. Plausibly children born in winter have sufficiently different experiences to children born in summer so that there is a very small overall ‘birth season’ effect, which correlates perfectly with the zodiac sign.

(1b) From that bogus base they then need to expand in a way that seems plausible to them and current unbelievers. So, by necessity, they add true elements to their system, based on their own experience and observations. (This makes it sound more agenda driven than it is, IMO. Like everyone else astrologers try to make sense of the world around them and attempt to include regularities they believe to exist into their worldview.)

(2) Freud believed the ego, the id and the super-ego are theoretical constructs of such importance that they might as well be actual agents in the mind. That’s bogus, too, but the therapy framework built on top of it works. (Somewhat.)

And just like astrologers are hampered in their attempts to explain things by having to relate it back to the influence of distant stars, Freudian psychoanalysis was and is hampered by the need to connect new ideas back to its founder’s revelations.

(3) If you take something modern like Myers-Briggs types or the Big Five model the issue persists. ‘Progress’ here consists of avoiding speculation as to the causal grounding of those theories and in some cases an agnostic stance on the psychological ‘existence’ (for want of a better term) of the construct, i.e. like intelligence, extraversion is that which the extraversion questionaire measures.

2 & 3 work together, in that if I can accept Freudian psychotherapists I have no strong arguments against astrologers, and I have to accept Freudians (with caveats) because nobody else has offered a better solution. The ‘best’ solution is not to talk about the problem.

That doesn’t mean I believe in astrology, just that, as long as they don’t talk about the actual stars astrologers may have as valuable insights, expressed through their symbol systems, as psychologists in general and the proponents of new therapeutic approaches in particular.

Regarding (1a), sure it’s vaguely plausible that there is a birth season effect loosely relating personality to zodiac signs, but I’ve never seen any evidence of it. Also, astrologers also believe that things like planetary conjunctions have effects, and there isn’t any plausible correlate to this.